United We Stand

December 19, 1919 - September 29, 2004

The Husband

The father.

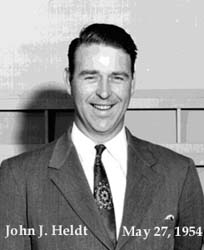

EULOGY FOR JOHN JOURDAN HELDT

by Nicholas Heldt

John Jourdan Heldt, my dad, was born December 19, 1919. He was 84 years old when he died. I want to tell you a little about the story of his life because we should remember.

When dad was 10 years old, his father, Carl Anton Heldt died, on February 1, 1930. At that time, dad’s older brother, Carl Jr., was 14 years old. Dad was 10. And their sister Toni was just 2 years old. The three children were raised by their mother, Marcella Bosse Heldt.

Dad graduated from high school in 1937 and went to work. College wasn’t an option when he graduated from high school.

In 1942, after America entered World War II, dad joined the Army as a private at age 22. He served in the 66th Regiment of the 71st Infantry Division in France, Germany and Austria. He was promoted through the ranks to Staff Sergeant and then received a field promotion to Second Lieutenant. The 71st Infantry Division was the Allied unit that liberated 18,000 Jews from the concentration camp called Gunskirchen Lager just north of Lambach, Austria, in May 1945.

When he was discharged from the Army he returned home and married our mom, Marguerite. They were married on May 11, 1946, by Reverend Dobleston at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Evansville, where dad had been baptized and confirmed and had been a lifelong member.

As a veteran, dad was entitled to the G.I. Bill to help pay for college. He enrolled in Evansville College and graduated in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering. Jake was born that year, in 1949.

In 1950, dad was recalled by the Army to serve in Korea. A few weeks after I was born, dad returned to the Army at age 31, leaving two small children at home. He served 14 months in Korea as a First Lieutenant in the Combat Engineers of the 3rd Infantry Division and was awarded a Bronze Star.

Another person might have thought he had been dealt a tough hand – to have a father who died young, and to have his life disrupted not once, but twice, by Army service during wartime. But dad felt blessed: blessed that his mother was a wonderful woman, who was a great storyteller, like dad, with a sense of humor, a strong faith, and a strong sense of family; blessed that he had married a wonderful, strong woman – Marguerite – with an equally strong sense of family. Dad also felt blessed that the G.I. Bill had made it possible for him to go to college. I never heard dad say just that he went to college. He always said he “went to college on the G.I. Bill” and he was grateful for it.

Dad certainly made the most of his college on the G.I. Bill, by continuing his education. In 1961, at age 41, with six children at home, and working full time, he earned his masters degree in engineering at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. In 1975, at age 55, he earned his first Ph.D. in engineering. And in 1986, at age 66, he earned his second Ph.D. in engineering.

Dad was proud of his Ph.D.s and sometime he like to call himself Dr. John. But when he did, it was a little tongue-in-cheek, his way of saying, “let’s keep things in perspective.”

Dad was very proud of the work he did. He was awarded two patents. He learned quality control on the job and then began to write on the subject and to teach the subject in local colleges and later around the country and around the world. He published more than 50 articles on the subject and several textbooks.

Dad’s work took the family away from Indiana, first to Texas and then to California. Whenever we moved, the first thing dad did was to find a place to live. And the second thing he did was to join the nearest Lutheran church, Missouri Synod. It wasn’t common to hear dad talk about his faith. But it was very common to see him being faithful. We all dressed for church every Sunday. I remember times when all my sisters had identical dresses for church and my mom had a matching dress. And as we walked into church each Sunday dad would hand each of the kids a dime that we were expected to put into the collection plate so that we would learn the habits of charity.

Dad was very proud to be able to support the church. Just as he was proud to have served his country in World War II and Korea, he was proud to pay his taxes without complaint, and he was proud to be able to give to charity and to support the church. One year, dad was audited by the I.R.S. The I.R.S. has guidelines on the percentage range of income that was normal to give to charity. Year in and year out, dad gave a higher than normal percentage of his income to charity and so one year he was audited. Dad was quite proud to tell the story that when the I.R.S. audited him the end result was that the government owed him money.

When we moved from Texas to California there were six kids in the family. Marci, named after his mother Marcella, came the following year. Somehow a local Catholic church had gotten the notion that our family, with six kids, was a Catholic family and that we should be attending mass at the Catholic church. Dad tried to explain that we belonged to another church and that our spiritual needs were taken care of. But the Catholic church was persistent and continued to call him about bringing the family to mass. Finally, dad wrote them a letter assuring them that the family’s spiritual needs were being met. But he enclosed a check to the Catholic church as a contribution because he admired their persistence to serve the community. Dad was generous like this throughout his life. In all his life, I have never known him to do a selfish thing.

Wherever they came from, from his mother or from his faith, dad had “family values” in the old-fashioned sense. Today “family values” is a phrase that has taken on some political meaning and seems to be a straight-jacketed idea of only one kind of “family,” or only one rigid set of “values.” Dad’s sense of family values, and mom’s as well, was to give each of us our own moral compass and then to respect and be supportive of any choice any of us made if it was based on our own genuine sense of moral rightness, even if that was not dad’s sense. In the 1960s this nation fought a war in Vietnam. I served in that war. But my brother, Jake, objected to that war and refused service. Each of us accepted the consequences of our choice. Dad was proud of both of us. Dad was proud of all his children and uncritically welcomed all of our spouses and partners as part of the family. I look at the devotion and affection shown by my sisters, especially Becky and Peggy and Janet, toward our dad as his health failed and I see a legacy of family values that has been passed from one generation to the next.

Until his health failed him and he couldn’t continue any more, every Saturday night was family dinner night out with dad. This went on for 40 years, every Saturday night. When we were kids we would go out as a family to a cafeteria on Saturday nights. As the kids got older, and we had families of our own, Saturday night dinner out would be at a pizza parlor or a smorgasbord, or an all-you-can-eat place, a German place if he could find one. Every Saturday night everyone was welcome, and 10 or 20 or 30 of us would show up for dinner on dad, every Saturday night. That was dad’s idea of family values: 1. everyone is welcome; 2. dad got to pay for it, and he liked paying for it; and 3. mom didn’t have to cook or clean up. That’s pretty nearly a perfect world in dad’s idea of things.

Dad was a highly educated engineer and inventor and an author and a teacher who won prizes and awards for his professional work. He enjoyed his work and he liked to tell stories about it, just as he enjoyed a good story on almost any subject. Dad’s life is a good story worth remembering about doing the right thing, about understanding his responsibilities and then living up to them, cheerfully.

When I was a teenager, whenever I left the house, dad always said the same thing to me. He must have said this to me a couple of hundred times. Maybe he thought I would forget it. He said: “Conduct yourself in a way that brings honor on yourself and your family.” Surely dad lived by that standard and brought honor to himself and his family.

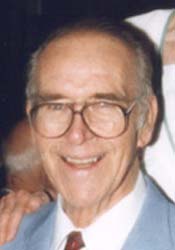

The generation after mine, my kids and their cousins, dad’s grandchildren, have only known their grandfather in the last quarter of his life or less, when his health and vigor began to fail. Some of you grandchildren may not be able to remember him as a big, robust man with a booming laugh, as he was most of his life. But the story of his life is a simple one and a good one we should all try to make our own: make the most of what you are given; love your family; be generous to others; enjoy your work; understand your responsibilities and live up to them, cheerfully!

All his adult life, if you asked dad in an ordinary greeting, “How are you?” he would always answer, “Marvelous,” or he’d say, “Wonderful.” In the last couple of years, as his health failed, if you asked him, “How are you?” and you pressed him for a literal answer, dad might admit he had seen better days; but, he’d say, he was still, “marvelous,” he was still, “wonderful.” Dad had it right. He was wonderful. We should celebrate his rich life and his accomplishments. But we will miss him.